BUSINESS NEWS - South Africans tend to think they are worse off than most in the world. We hear and read about consumer indebtness as the public relation machines of debt collectors and debt counsellors shriek on about the ‘poor consumers’ and their debt crises.

Meanwhile, government spin doctors are about to go into overdrive about how the state plans to control its growing debt burden.

Debt is an ordinary and necessary part of modern economic life.

There is no economy that I know of without financial obligation. Three major role players make use of debt in the economy – consumers, governments and companies. (For this article we leave out the complex world of intra- financial-market debt such as hedge funds and banks.)

In South Africa, the consumer is often thought to have a massive debt problem and while consumers did struggle with debt during the peak before the National Credit Act started to operate, the fact is that compared to developed world standards our consumers have never had the same level of financial obligations.

As can be seen by the graph above, consumers in South Africa have less debt than the world average and have been far below the world average for the total period for which I have data.

It is worth noting that at present, in the last two years or so, South African consumers also have lower debt levels than our emerging market peers. We are an upper middle-income country, and it would not be unexpected to have a slightly higher household debt-to-GDP ratio than emerging market households.

The Bank for International Settlements provides this data set, and it gives a good 11-year history. It shows that at the end of the 2nd quarter of 2018 the South African household had a debt level that was 2.7% lower as a percentage of GDP than the average emerging market household.

The South African consumer has on average a lower debt burden than their emerging market counterparts in relative terms and, certainly by any measure, the developed world consumer. Let me say this again – South Africa has a well-organised credit market and good counselling and debt management institutions, along with very good legislation.

There will always be people in trouble and here too I believe we have a good system to help and educate consumers. We have good credit bureaus and good information systems at banks too. So SA consumer debt is in general not a problem, and is low by international comparison.

Government debt going in the wrong direction

Government debt in South Africa is now about 10% higher as a percentage of GDP.

As the commodity boom came to an end South African government debt overtook the debt level of our emerging market peers. That was more or less the time that South African debt ratings started to decline.

The rating declines make sense in light of the fact that emerging markets do tend to have lower debt levels than advanced countries, which can afford to have higher debt levels due to higher income levels that can be tapped to pay off the borrowing.

The fact that SA now has a government debt-to-GDP level that is 10% higher than our emerging market peers – and which is still growing at a much faster rate than nominal GDP – means SA will be ranked below other emerging markets until its GDP grows quicker than its government debt.

The interesting thing here is that state guarantees are not part of this data for either emerging markets or SA. I do not have the emerging market information on state guarantees but SA certainly has a large state guarantee level of about 10%, which should be added to this level.

Adding the guarantees would take SA government debt to a level that is nearly as high as the world average, but with only 75% of the world’s per capita income. The pace of growth is estimated to be about 3.5% above GDP growth, which means that by the middle of this year SA could have a higher debt level than the world average (if guarantees are taken into account).

On current trends, these comparisons tell me that the likelihood of further downgrades remains high. Perhaps by the end of 2019 this will become clear.

Corporate debt levels – the known surprise

I hear readers shout that a known surprise cannot be … well, a surprise. But the surprise is not about South African company debt levels, which we know are going to be low as corporate confidence is lacking (partly due to uncertainty and next-to-nothing profit margins).

No, the surprise is the high level of corporate debt in emerging markets. This shows that as our peers grow faster than us, their corporate sectors commit not just large parts of their savings, but even larger levels of debt.

South Africa Inc has about 40% of the level of debt of our emerging market peers, which also have more obligations on average than the world’s non-financial corporates.

Emerging markets have been growing at over 4.5% for the last 25 years or so, and that has led to a lot of confidence in the future rate of growth, which again helps these economies to obtain capital from banks and other fund managers.

Moreover, keep in mind that South African companies have access to deep financial markets via the JSE, the world’s 18th largest stock exchange.

This is aided by venture capital, which assists start-up firms, as well as an active over-the-counter market and the private equity sector.

So while many emerging markets have two to three times the loans from funders, South African firms have higher equity funding generally.

However, equity funding is not going to compensate for the overall low levels of funding for firms today when compared to the average of the emerging markets.

So South Africa – with its lack of business confidence, lower profit margins, and market uncertainties – will not see growth kickstarted until some of the factors constraining growth are addressed.

Wealthy myths

In South Africa, it is standard practice to claim poverty and decry the rich while claiming victimhood.

The more one claims poverty, and the more we hear of poor and debt-struck underpaid citizens, the better for a government that has its eye on our collective assets.

To explain my scornful sentence above let me start by placing our pension fund assets in context.

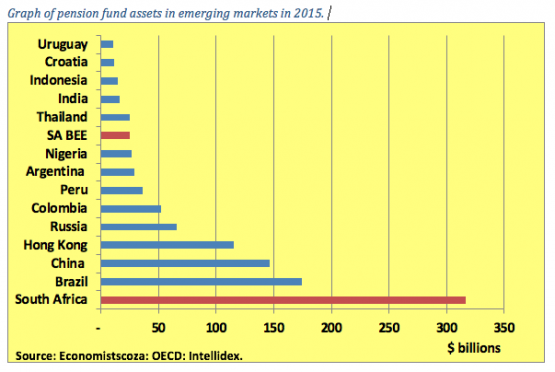

South Africa has the eighth largest pot of pension fund assets measured in US dollars in the world today. SA has more pension assets than any emerging market out there.

Yes, even Germany – the world’s fourth largest economy and generally seen as a very wealthy country – has less than South Africa.

This data is measured every year by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), along with other sources such as Willis Towers Watson, and it is clear that SA’s pension assets are the country’s crown jewels.

The value of South Africa’s pension fund assets is nearly twice the size of the next emerging market, and while Chinese pension assets are the fastest growing due to both market growth and growth in investments in retirement products due to ageing, South Africa’s pension assets are still the largest by a country mile.

Per capita, SA’s pension funds assets are the highest in the emerging market as far as can be ascertained. Also, a larger share of the adult population is estimated to have some form of retirement savings in South Africa; our pension assets have 16.5 million accounts, which we believe represent about 11 to 12 million people.

Interestingly if one takes the 2015 value of BEE assets in the 100 largest JSE companies, this alone would be the 10th largest pension asset in the emerging market universe. The BEE assets are, for example, bigger than the entire pension assets of India, a country with about 24 times SA’s population.

This retirement asset is a drawcard, and a good source for funding for equities and debt securities (both private and public). It is also a reason why the South African economy has a strong and healthy financial sector.

The problem, of course, is that governments often have a huge need for funding without the same commitment to above-inflation investment returns.

A decade ago I wrote about this pension pile, noting that it is a large and positive asset for SA, but the only people who seemed to notice were foreigners. A Russian researcher spoke at length with me on this and added that it could be used to fund government infrastructure. Shortly thereafter the nuclear option was on the table, with some saying it would not need government funding and would be funded by the suppliers who would, of course, get private sector funding (read SA pension funds).

The thing about prescribed assets is that they become attractive to governments that are looking to avoid the International Monetary Fund as that would bring much-needed oversight to government spending.

Home ownership is good but could be better

In the table below are 21 emerging market countries for which home ownership rates could be obtained after 2010 (Brazil is stuck at 2008, after which many ownership rates dropped, but has been kept in for comparison, while China was left out due to a methodology dispute).

The fact that over three million South African families stay in government-owned houses is something that could push the SA ownership rate beyond 80% at the stroke of a pen.

The other factor that complicates SA home ownership is that about two million families stay on traditional land, and although many have formal housing structure, ownership belongs to the tribal elder and people only get permission to occupy the house. They cannot get funding or transfer ownership in a modern sense.

Taking this into account one can assume then that SA’s home ownership rate can be improved upon without big infrastructure spending.

The typical adult in South Africa would be the 62nd most wealthy adult in the world due mainly to our great pension assets and partly to our home ownership rates. However, this ranking dropped from the mid-50s about a decade ago. Still, to be 62nd out of 140-odd countries means the typical South African is still richer than more than half of the world.

Among our emerging market peers, a typical South African is the 27th richest out of 103 countries. (Incidentally, South Africans are on average the 25th richest emerging market citizens and 59th in the world, but we are using the median to better display the real SA citizen).

As can be seen above, the only one of our Brics partners to have a higher wealth per typical adult is China, whose average adult is about a decade older than the average South African adult. Interestingly, one can see how Russia struggles as its history of low home ownership and financial assets undermine wealth creation in a country where adults are more than a decade older than South Africans (age plays a vital role in the growth of assets).

In conclusion, South Africa has a wealth of assets but we concentrate on what we don’t have and what the rich do have, while the actual warnings that we should heed are that prescribed assets, theft and corruption make South Africans less wealthy.

South Africans are not deficient in world wealth terms, and certainly not in emerging market terms.

Be aware that in 2008 South Africans were more affluent than the Polish, the Chinese and just 10% behind an adult in Chile. The typical person in Venezuela was however then wealthier than a South African, as was someone from Tunisia.

By 2018 Venezuela was no longer measured, but Poland and China had overtaken South Africa and Tunisians had fallen below South Africans. South Africa fell just three places as it is probably ahead of Venezuela now.

Things can and will change, and falsehoods often lead to destruction.

Wealth is hard-earned and a fall is hard to recover from. Do not allow the myths about poverty reduce our richness. Rather transfer the houses we have and make BEE beneficiaries real shareholders and not held to ransom by a few ‘new style chiefs’.

We have to make it all work. That would help South Africans a lot more than false shouting.

Mike Schüssler is chief economist at Economists.co.za.